what is the position in the world today of nations that are heirs to european christendom?

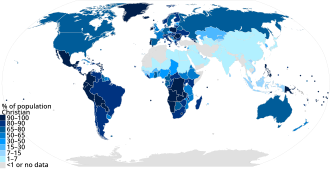

Christianity – Percentage of population by country (2014 data)

Christendom [1] [2] historically refers to the "Christian world": Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates,[3] prevails,[1] or is culturally intertwined with.

Since the spread of Christianity from the Levant to Europe and North Africa during the early Roman Empire, Christendom has been divided in the pre-existing Greek East and Latin West. Consequently, dissimilar versions of the Christian religion arose with their own beliefs and practices, centred around the cities of Rome (Western Christianity, whose community was called Western or Latin Christendom[4]) and Constantinople (Eastern Christianity, whose community was called Eastern Christendom[5]). From the 11th to 13th centuries, Latin Christendom rose to the fundamental role of the Western earth.[6] The history of the Christian globe spans about 1,700 years and includes a diverseness of socio-political developments, also every bit advances in the arts, architecture, literature, science, philosophy, and technology.[vii] [8] [9]

The term usually refers to the Centre Ages and to the Early Modern flow during which the Christian world represented a geopolitical ability that was juxtaposed with both the pagan and especially the Muslim earth.

Terminology [edit]

The Anglo-Saxon term crīstendōm appears to have been invented in the 9th century by a scribe somewhere in southern England, possibly at the court of rex Alfred the Bully of Wessex. The scribe was translating Paulus Orosius' book History Against the Pagans (c. 416) and in demand for a term to express the concept of the universal civilization focused on Jesus Christ.[10] Information technology had the sense at present taken past Christianity (as is yet the case with the cognate Dutch christendom,[11] where it denotes mostly the faith itself, but similar the German Christentum.[12]

The current sense of the word of "lands where Christianity is the dominant religion"[three] emerged in Tardily Centre English (by c. 1400).[thirteen]

Canadian theology professor Douglas John Hall stated (1997) that "Christendom" [...] means literally the dominion or sovereignty of the Christian organized religion."[3] Thomas John Curry, Roman Cosmic auxiliary bishop of Los Angeles, defined (2001) Christendom as "the system dating from the 4th century by which governments upheld and promoted Christianity."[14] Curry states that the end of Christendom came about because modern governments refused to "uphold the teachings, community, ethos, and practice of Christianity."[14] British church historian Diarmaid MacCulloch described (2010) Christendom as "the wedlock between Christianity and secular ability."[xv]

Christendom was originally a medieval concept which has steadily evolved since the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the gradual ascent of the Papacy more in religio-temporal implications practically during and after the reign of Charlemagne; and the concept permit itself exist lulled in the minds of the staunch believers to the archetype of a holy religious space inhabited by Christians, blessed by God, the Heavenly Father, ruled by Christ through the Church and protected by the Spirit-body of Christ; no wonder, this concept, as included the whole of Europe and then the expanding Christian territories on earth, strengthened the roots of Romance of the greatness of Christianity in the world.[xvi]

There is a mutual and nonliteral sense of the word that is much like the terms Western globe, known world or Complimentary World. The notion of "Europe" and the "Western World" has been intimately connected with the concept of "Christianity and Christendom"; many even aspect Christianity for being the link that created a unified European identity.[17]

History [edit]

Rising of Christendom [edit]

This T-and-O map, which abstracts the then known globe to a cross inscribed within an orb, remakes geography in the service of Christian iconography. More detailed versions identify Jerusalem at the center of the world.

Early Christianity spread in the Greek/Roman world and beyond as a 1st-century Jewish sect,[18] which historians refer to as Jewish Christianity. It may exist divided into two distinct phases: the apostolic menstruum, when the first apostles were alive and organizing the Church, and the post-churchly menstruum, when an early episcopal structure developed, whereby bishoprics were governed by bishops (overseers).

The post-churchly period concerns the time roughly after the death of the apostles when bishops emerged every bit overseers of urban Christian populations. The earliest recorded utilize of the terms Christianity (Greek Χριστιανισμός ) and catholic (Greek καθολικός ), dates to this period, the 2nd century, attributed to Ignatius of Antioch c. 107.[19] Early Christendom would close at the end of imperial persecution of Christians later on the ascension of Constantine the Bully and the Edict of Milan in AD 313 and the Outset Council of Nicaea in 325.[ citation needed ]

According to Malcolm Muggeridge (1980), Christ founded Christianity, but Constantine founded Christendom.[20] Canadian theology professor Douglas John Hall dates the 'inauguration of Christendom' to the 4th century, with Constantine playing the chief role (then much then that he equates Christendom with "Constantinianism") and Theodosius I (Edict of Thessalonica, 380) and Justinian I[a] secondary roles.[22]

Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages [edit]

![]()

Spread of Christianity by Advertisement 600 (shown in dark blue is the spread of Early Christianity upwards to Advertising 325)

"Christendom" has referred to the medieval and renaissance notion of the Christian world as a polity. In essence, the primeval vision of Christendom was a vision of a Christian theocracy, a authorities founded upon and upholding Christian values, whose institutions are spread through and over with Christian doctrine. In this period, members of the Christian clergy wield political dominance. The specific human relationship between the political leaders and the clergy varied simply, in theory, the national and political divisions were at times subsumed under the leadership of the church as an institution. This model of church-state relations was accepted by diverse Church building leaders and political leaders in European history.[23]

The Church gradually became a defining institution of the Roman Empire.[24] Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313 proclaiming toleration for the Christian faith, and convoked the Showtime Council of Nicaea in 325 whose Nicene Creed included belief in "ane holy catholic and apostolic Church". Emperor Theodosius I made Nicene Christianity the state church building of the Roman Empire with the Edict of Thessalonica of 380.[25]

Every bit the Western Roman Empire disintegrated into feudal kingdoms and principalities, the concept of Christendom inverse equally the western church became one of five patriarchates of the Pentarchy and the Christians of the Eastern Roman Empire developed.[ clarification needed ] The Byzantine Empire was the terminal breastwork of Christendom.[26] Christendom would take a plow with the rise of the Franks, a Germanic tribe who converted to the Christian faith and entered into communion with Rome.

On Christmas Day 800 AD, Pope Leo Iii crowned Charlemagne, resulting in the creation of another Christian male monarch abreast the Christian emperor in the Byzantine state.[27] [ unreliable source? ] The Carolingian Empire created a definition of Christendom in juxtaposition with the Byzantine Empire, that of a distributed versus centralized culture respectively.[28]

The classical heritage flourished throughout the Centre Ages in both the Byzantine Greek East and the Latin West. In the Greek philosopher Plato's platonic state there are 3 major classes, which was representative of the thought of the "tripartite soul", which is expressive of iii functions or capacities of the human soul: "reason", "the spirited element", and "appetites" (or "passions"). Will Durant made a convincing instance that certain prominent features of Plato'south ideal community where discernible in the organization, dogma and effectiveness of "the" Medieval Church building in Europe:[29]

... For a k years Europe was ruled by an order of guardians considerably like that which was visioned past our philosopher. During the Center Ages it was customary to allocate the population of Christendom into laboratores (workers), bellatores (soldiers), and oratores (clergy). The last group, though small in number, monopolized the instruments and opportunities of civilisation, and ruled with well-nigh unlimited sway half of the most powerful continent on the globe. The clergy, similar Plato'southward guardians, were placed in authorisation... by their talent equally shown in ecclesiastical studies and administration, by their disposition to a life of meditation and simplicity, and ... by the influence of their relatives with the powers of land and church building. In the latter half of the period in which they ruled [800 AD onwards], the clergy were as free from family cares as fifty-fifty Plato could desire [for such guardians]... [Clerical] Celibacy was part of the psychological structure of the power of the clergy; for on the i hand they were unimpeded by the narrowing egoism of the family, and on the other their apparent superiority to the call of the mankind added to the awe in which lay sinners held them.... [29] In the latter half of the period in which they ruled, the clergy were as costless from family unit cares equally even Plato could desire.[29]

Later Middle Ages and Renaissance [edit]

After the collapse of Charlemagne's empire, the southern remnants of the Holy Roman Empire became a drove of states loosely continued to vatican city of Rome. Tensions betwixt Pope Innocent III and secular rulers ran high, as the pontiff exerted control over their temporal counterparts in the due west and vice versa. The pontificate of Innocent III is considered the height of temporal ability of the papacy. The Corpus Christianum described the then-electric current notion of the community of all Christians united nether the Roman Cosmic Church building. The community was to be guided past Christian values in its politics, economics and social life.[thirty] Its legal footing was the corpus iuris canonica (body of catechism police force).[31] [32] [33] [34]

In the East, Christendom became more defined as the Byzantine Empire'southward gradual loss of territory to an expanding Islam and the muslim conquest of Persia. This caused Christianity to become important to the Byzantine identity. Before the Due east–West Schism which divided the Church building religiously, there had been the notion of a universal Christendom that included the East and the West. After the East–West Schism, hopes of regaining religious unity with the Due west were concluded past the Fourth Crusade, when Crusaders conquered the Byzantine majuscule of Constantinople and hastened the decline of the Byzantine Empire on the path to its destruction.[35] [36] [37] With the breakup of the Byzantine Empire into individual nations with nationalist Orthodox Churches, the term Christendom described Western Europe, Catholicism, Orthodox Byzantines, and other Eastern rites of the Church.[38] [39]

The Catholic Church building's peak of say-so over all European Christians and their common endeavours of the Christian community — for case, the Crusades, the fight against the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula and against the Ottomans in the Balkans — helped to develop a sense of communal identity against the obstruction of Europe's deep political divisions. The popes, formally just the bishops of Rome, claimed to be the focus of all Christendom, which was largely recognised in Western Christendom from the 11th century until the Reformation, but not in Eastern Christendom.[40] Moreover, this authorization was besides sometimes abused, and fostered the Inquisition and anti-Jewish pogroms, to root out divergent elements and create a religiously uniform customs.[ citation needed ] Ultimately, the Inquisition was done away with past order of Pope Innocent Iii.[41]

Christendom ultimately was led into specific crisis in the late Middle Ages, when the kings of France managed to establish a French national church during the 14th century and the papacy became ever more aligned with the Holy Roman Empire of the High german Nation. Known as the Western Schism, western Christendom was a carve up between iii men, who were driven by politics rather than any real theological disagreement for simultaneously challenge to be the true pope. The Avignon Papacy adult a reputation for corruption that estranged major parts of Western Christendom. The Avignon schism was ended by the Council of Constance.[42]

Before the modernistic menstruation, Christendom was in a general crisis at the fourth dimension of the Renaissance Popes because of the moral laxity of these pontiffs and their willingness to seek and rely on temporal ability every bit secular rulers did.[ citation needed ] Many in the Catholic Church building's hierarchy in the Renaissance became increasingly entangled with insatiable greed for material wealth and temporal power, which led to many reform movements, some merely wanting a moral reformation of the Church's clergy, while others repudiated the Church and separated from it in order to form new sects.[ commendation needed ] The Italian Renaissance produced ideas or institutions by which men living in order could be held together in harmony. In the early 16th century, Baldassare Castiglione (The Book of the Courtier) laid out his vision of the ideal gentleman and lady, while Machiavelli cast a jaundiced center on "la verità effetuale delle cose" — the actual truth of things — in The Prince, composed, humanist fashion, chiefly of parallel ancient and modern examples of Virtù. Some Protestant movements grew upward along lines of mysticism or renaissance humanism (cf. Erasmus). The Cosmic Church cruel partly into general neglect nether the Renaissance Popes, whose inability to govern the Church by showing personal example of high moral standards prepare the climate for what would ultimately become the Protestant Reformation.[43] During the Renaissance, the papacy was mainly run by the wealthy families and besides had strong secular interests. To safeguard Rome and the connected Papal States the popes became necessarily involved in temporal matters, even leading armies, every bit the great patron of arts Pope Julius II did. Information technology during these intermediate times popes strove to make Rome the capital of Christendom while projecting it, through fine art, architecture, and literature, as the heart of a Aureate Age of unity, social club, and peace.[44]

Professor Frederick J. McGinness described Rome as essential in understanding the legacy the Church building and its representatives encapsulated best by The Eternal City:

No other city in Europe matches Rome in its traditions, history, legacies, and influence in the Western world. Rome in the Renaissance under the papacy non only acted as guardian and transmitter of these elements stemming from the Roman Empire but besides assumed the office as artificer and interpreter of its myths and meanings for the peoples of Europe from the Middle Ages to modern times... Under the patronage of the popes, whose wealth and income were exceeded only by their ambitions, the metropolis became a cultural center for principal architects, sculptors, musicians, painters, and artisans of every kind...In its myth and message, Rome had become the sacred city of the popes, the prime symbol of a triumphant Catholicism, the center of orthodox Christianity, a new Jerusalem.[45]

Information technology is clearly noticeable that the popes of the Italian Renaissance have been subjected by many writers with an overly harsh tone. Pope Julius Two, for instance, was non only an effective secular leader in military machine affairs, a deviously effective politician but foremost one of the greatest patron of the Renaissance period and person who also encouraged open criticism from noted humanists.[46]

The blossoming of renaissance humanism was made very much possible due to the universality of the institutions of Catholic Church and represented by personalities such every bit Pope Pius II, Nicolaus Copernicus, Leon Battista Alberti, Desiderius Erasmus, sir Thomas More than, Bartolomé de Las Casas, Leonardo da Vinci and Teresa of Ávila. George Santayana in his work The Life of Reason postulated the tenets of the all encompassing order the Church had brought and every bit the repository of the legacy of classical artifact:[47]

The enterprise of individuals or of pocket-size aristocratic bodies has meantime sown the world which we phone call civilised with some seeds and nuclei of club. There are scattered well-nigh a multifariousness of churches, industries, academies, and governments. But the universal order one time dreamt of and nominally most established, the empire of universal peace, all-permeating rational art, and philosophical worship, is mentioned no more. An unformulated conception, the prerational ethics of private privilege and national unity, fills the groundwork of men'southward minds. It represents feudal traditions rather than the tendency actually involved in contemporary manufacture, scientific discipline, or philanthropy. Those nighttime ages, from which our political practice is derived, had a political theory which we should practice well to study; for their theory about a universal empire and a Catholic church was in turn the echo of a former historic period of reason, when a few men conscious of ruling the world had for a moment sought to survey information technology every bit a whole and to rule it justly.[47]

Reformation and Early Modern era [edit]

Developments in western philosophy and European events brought alter to the notion of the Corpus Christianum. The Hundred Years' State of war accelerated the process of transforming French republic from a feudal monarchy to a centralized country. The rise of strong, centralized monarchies[48] denoted the European transition from feudalism to capitalism. Past the end of the Hundred Years' War, both France and England were able to raise enough money through revenue enhancement to create independent standing armies. In the Wars of the Roses, Henry Tudor took the crown of England. His heir, the absolute rex Henry Eight establishing the English church.[49]

In modern history, the Reformation and rise of modernity in the early on 16th century entailed a change in the Corpus Christianum. In the Holy Roman Empire, the Peace of Augsburg of 1555 officially ended the idea amongst secular leaders that all Christians must exist united nether i church. The principle of cuius regio, eius religio ("whose the region is, his religion") established the religious, political and geographic divisions of Christianity, and this was established with the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, which legally ended the concept of a single Christian hegemony in the territories of the Holy Roman Empire, despite the Cosmic Church's doctrine that it lonely is the ane true Church building founded by Christ. Subsequently, each government determined the organized religion of their own land. Christians living in states where their denomination was not the established ane were guaranteed the right to practice their organized religion in public during allotted hours and in individual at their volition.[ citation needed ] At times there were mass expulsions of dissenting faiths as happened with the Salzburg Protestants. Some people passed every bit adhering to the official church building, just instead lived as Nicodemites or crypto-protestants.

The European wars of religion are commonly taken to take ended with the Treaty of Westphalia (1648),[50] or arguably, including the Ix Years' War and the State of war of the Spanish Succession in this menses, with the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713.[ citation needed ] [51] In the 18th century, the focus shifts away from religious conflicts, either betwixt Christian factions or confronting the external threat of Islamic factions.[ citation needed ]

End of Christendom [edit]

The European Phenomenon, the Age of Enlightenment and the formation of the great colonial empires together with the beginning decline of the Ottoman Empire mark the stop of the geopolitical "history of Christendom".[ citation needed ] Instead, the focus of Western history shifts to the development of the nation-country, accompanied past increasing disbelief and secularism, culminating with the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars at the turn of the 19th century.[ citation needed ]

Writing in 1997, Canadian theology professor Douglas John Hall argued that Christendom had either fallen already or was in its death throes; although its end was gradual and not equally clear to pivot down as its quaternary-century establishment, the "transition to the post-Constantinian, or post-Christendom, situation (...) has already been in process for a century or ii," beginning with the 18th-century rationalist Enlightenment and the French Revolution (the first attempt to topple the Christian establishment).[22] American Catholic bishop Thomas John Curry stated (2001) that the end of Christendom came about because modern governments refused to "uphold the teachings, community, ethos, and practise of Christianity."[14] He argued the Get-go Amendment to the United states Constitution (1791) and the Second Vatican Council'south Proclamation on Religious Freedom (1965) are two of the most of import documents setting the stage for its end.[14] Co-ordinate to British historian Diarmaid MacCulloch (2010), Christendom was 'killed' by the Commencement World War (1914–18), which led to the fall of the three master Christian empires (Russian, German and Austrian) of Europe, as well equally the Ottoman Empire, rupturing the Eastern Christian communities that had existed on its territory. The Christian empires were replaced past secular, even anti-clerical republics seeking to definitively keep the churches out of politics. The just surviving monarchy with an established church, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, was severely damaged past the state of war, lost most of Ireland due to Catholic–Protestant infighting, and was starting to lose grip on its colonies.[15]

Classical culture [edit]

Western civilisation, throughout most of its history, has been nearly equivalent to Christian civilisation, and many of the population of the Western hemisphere could broadly be described as cultural Christians. The notion of "Europe" and the "Western World" has been intimately connected with the concept of "Christianity and Christendom"; many even attribute Christianity for being the link that created a unified European identity.[17] Historian Paul Legutko of Stanford Academy said the Catholic Church is "at the heart of the development of the values, ideas, science, laws, and institutions which found what nosotros call Western civilization."[nine]

Though Western culture contained several polytheistic religions during its early on years under the Greek and Roman Empires, as the centralized Roman power waned, the dominance of the Catholic Church was the only consistent force in Western Europe.[52] Until the Age of Enlightenment,[53] Christian culture guided the class of philosophy, literature, art, music and scientific discipline.[52] [seven] Christian disciplines of the corresponding arts take subsequently developed into Christian philosophy, Christian fine art, Christian music, Christian literature etc. Fine art and literature, law, pedagogy, and politics were preserved in the teachings of the Church building, in an environment that, otherwise, would have probably seen their loss. The Church building founded many cathedrals, universities, monasteries and seminaries, some of which go on to exist today. Medieval Christianity created the commencement mod universities.[54] [55] The Catholic Church building established a hospital system in Medieval Europe that vastly improved upon the Roman valetudinaria.[56] These hospitals were established to cater to "particular social groups marginalized by poverty, sickness, and age," according to historian of hospitals, Guenter Risse.[57] Christianity also had a strong impact on all other aspects of life: wedlock and family, education, the humanities and sciences, the political and social order, the economy, and the arts.[58]

Christianity had a significant impact on education and science and medicine as the church created the bases of the Western system of educational activity,[59] and was the sponsor of founding universities in the Western world as the university is generally regarded as an establishment that has its origin in the Medieval Christian setting.[60] [61] Many clerics throughout history have fabricated significant contributions to science and Jesuits in item accept made numerous significant contributions to the development of science.[62] [63] [64] The cultural influence of Christianity includes social welfare,[65] founding hospitals,[66] economics (as the Protestant work ethic),[67] [68] natural constabulary (which would later influence the creation of international police),[69] politics,[70] architecture,[71] literature,[72] personal hygiene,[73] [74] and family life.[75] Christianity played a role in ending practices common among pagan societies, such equally human cede, slavery,[76] infanticide and polygamy.[77]

Fine art and literature [edit]

Writings and poetry [edit]

Christian literature is writing that deals with Christian themes and incorporates the Christian globe view. This constitutes a huge body of extremely varied writing. Christian poetry is any poetry that contains Christian teachings, themes, or references. The influence of Christianity on poetry has been great in any area that Christianity has taken concord. Christian poems frequently directly reference the Bible, while others provide allegory.

[edit]

Christian art is fine art produced in an attempt to illustrate, supplement and portray in tangible grade the principles of Christianity. About all Christian groupings use or accept used fine art to some extent. The prominence of art and the media, style, and representations change; however, the unifying theme is ultimately the representation of the life and times of Jesus and in some cases the Old Testament. Depictions of saints are also common, especially in Anglicanism, Roman Catholicism, and Eastern Orthodoxy.

Illumination [edit]

An illuminated manuscript is a manuscript in which the text is supplemented past the addition of decoration. The earliest surviving substantive illuminated manuscripts are from the period Advertisement 400 to 600, primarily produced in Ireland, Constantinople and Italy. The majority of surviving manuscripts are from the Middle Ages, although many illuminated manuscripts survive from the 15th century Renaissance, along with a very limited number from Late Antiquity.

Most illuminated manuscripts were created equally codices, which had superseded scrolls; some isolated unmarried sheets survive. A very few illuminated manuscript fragments survive on papyrus. Most medieval manuscripts, illuminated or not, were written on parchment (most normally of calf, sheep, or goat skin), but virtually manuscripts of import enough to illuminate were written on the all-time quality of parchment, chosen vellum, traditionally made of unsplit calfskin, though high quality parchment from other skins was as well called parchment.

Iconography [edit]

Christian art began, about two centuries later Christ, by borrowing motifs from Roman Imperial imagery, classical Greek and Roman religion and popular art. Religious images are used to some extent by the Abrahamic Christian faith, and oftentimes contain highly complex iconography, which reflects centuries of accumulated tradition. In the Tardily Antiquarian menses iconography began to be standardised, and to chronicle more closely to Biblical texts, although many gaps in the canonical Gospel narratives were plugged with affair from the counterfeit gospels. Eventually the Church would succeed in weeding most of these out, but some remain, like the ox and ass in the Nativity of Christ.

An icon is a religious work of art, most ordinarily a painting, from Eastern Christianity. Christianity has used symbolism from its very beginnings.[78] In both Due east and West, numerous iconic types of Christ, Mary and saints and other subjects were developed; the number of named types of icons of Mary, with or without the infant Christ, was especially large in the East, whereas Christ Pantocrator was much the commonest prototype of Christ.

Christian symbolism invests objects or actions with an inner significant expressing Christian ideas. Christianity has borrowed from the common stock of significant symbols known to virtually periods and to all regions of the world. Religious symbolism is effective when it appeals to both the intellect and the emotions. Particularly of import depictions of Mary include the Hodegetria and Panagia types. Traditional models evolved for narrative paintings, including large cycles roofing the events of the Life of Christ, the Life of the Virgin, parts of the Old Testament, and, increasingly, the lives of pop saints. Especially in the West, a arrangement of attributes developed for identifying individual figures of saints by a standard advent and symbolic objects held past them; in the East they were more probable to identified by text labels.

Each saint has a story and a reason why he or she led an exemplary life. Symbols have been used to tell these stories throughout the history of the Church. A number of Christian saints are traditionally represented by a symbol or iconic motif associated with their life, termed an attribute or keepsake, in society to place them. The study of these forms part of iconography in Art history. They were particularly

Architecture [edit]

The structure of a typical Gothic cathedral.

Christian architecture encompasses a broad range of both secular and religious styles from the foundation of Christianity to the present day, influencing the blueprint and construction of buildings and structures in Christian culture.

Buildings were at start adapted from those originally intended for other purposes but, with the rise of distinctively ecclesiastical architecture, church building buildings came to influence secular ones which have frequently imitated religious compages. In the 20th century, the use of new materials, such as concrete, as well as simpler styles has had its outcome upon the blueprint of churches and arguably the flow of influence has been reversed. From the nascence of Christianity to the present, the most significant menstruum of transformation for Christian architecture in the west was the Gothic cathedral. In the east, Byzantine compages was a continuation of Roman compages.

Philosophy [edit]

Christian philosophy is a term to describe the fusion of various fields of philosophy with the theological doctrines of Christianity. Scholasticism, which means "that [which] belongs to the schoolhouse", and was a method of learning taught by the academics (or schoolhouse people) of medieval universities c. 1100–1500. Scholasticism originally started to reconcile the philosophy of the aboriginal classical philosophers with medieval Christian theology. Scholasticism is not a philosophy or theology in itself only a tool and method for learning which places accent on dialectical reasoning.

Christian civilization [edit]

Science, and particularly geometry and astronomy, was linked directly to the divine for nigh medieval scholars. Since these Christians believed God imbued the universe with regular geometric and harmonic principles, to seek these principles was therefore to seek and worship God.

Medieval weather condition [edit]

The Byzantine Empire, which was the most sophisticated civilisation during antiquity, suffered nether Muslim conquests limiting its scientific prowess during the Medieval flow. Christian Western Europe had suffered a catastrophic loss of cognition following the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Simply cheers to the Church scholars such as Aquinas and Buridan, the Due west carried on at least the spirit of scientific research which would later lead to Europe's taking the atomic number 82 in scientific discipline during the Scientific Revolution using translations of medieval works.

Medieval technology refers to the engineering used in medieval Europe under Christian dominion. Later the Renaissance of the 12th century, medieval Europe saw a radical change in the charge per unit of new inventions, innovations in the ways of managing traditional ways of production, and economical growth.[79] The period saw major technological advances, including the adoption of gunpowder and the astrolabe, the invention of spectacles, and greatly improved water mills, building techniques, agriculture in full general, clocks, and ships. The latter advances fabricated possible the dawn of the Historic period of Exploration. The development of water mills was impressive, and extended from agriculture to sawmills both for timber and stone, probably derived from Roman engineering science. Past the time of the Domesday Book, nigh big villages in Britain had mills. They as well were widely used in mining, as described by Georg Agricola in De Re Metallica for raising ore from shafts, burdensome ore, and even powering bellows.

Meaning in this respect were advances inside the fields of navigation. The compass and astrolabe forth with advances in shipbuilding, enabled the navigation of the Globe Oceans and thus domination of the worlds economic trade. Gutenberg's press printing made possible a dissemination of cognition to a wider population, that would not only pb to a gradually more than egalitarian guild, but 1 more able to boss other cultures, drawing from a vast reserve of knowledge and feel.

Renaissance innovations [edit]

During the Renaissance, great advances occurred in geography, astronomy, chemistry, physics, math, manufacturing, and engineering science. The rediscovery of aboriginal scientific texts was accelerated afterward the Fall of Constantinople, and the invention of printing which would democratize learning and allow a faster propagation of new ideas. Renaissance technology is the set of artifacts and customs, spanning roughly the 14th through the 16th century. The era is marked past such profound technical advancements like the printing press, linear perspectivity, patent constabulary, double crush domes or Bastion fortresses. Describe-books of the Renaissance artist-engineers such equally Taccola and Leonardo da Vinci requite a deep insight into the mechanical technology so known and practical.

Renaissance science spawned the Scientific Revolution; scientific discipline and technology began a wheel of common advocacy. The Scientific Renaissance was the early phase of the Scientific Revolution. In the 2-stage model of early on modern science: a Scientific Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries, focused on the restoration of the natural cognition of the ancients; and a Scientific Revolution of the 17th century, when scientists shifted from recovery to innovation. Some scholars and historians attributes Christianity to having contributed to the rise of the Scientific Revolution.[80] [81] [82] [83]

Demographics [edit]

Geographic spread [edit]

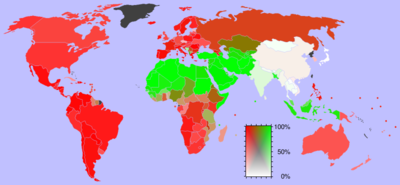

Relative geographic prevalence of Christianity versus Islam versus lack of either religion (2006).

In 2009, according to the Encyclopædia Britannica, Christianity was the bulk religion in Europe (including Russia) with 80%, Latin America with 92%, N America with 81%, and Oceania with 79%.[84] In that location are also big Christian communities in other parts of the world, such as Cathay, India and Central Asia, where Christianity is the second-largest religion after Islam. The Us is dwelling to the world's largest Christian population, followed by Brazil and Mexico.[85]

Many Christians not only live under, but besides have an official status in, a country religion of the post-obit nations: Argentina (Roman Catholic Church),[86] Armenia (Armenian Apostolic Church),[87] Costa Rica (Roman Catholic Church),[88] Denmark (Church building of Kingdom of denmark),[89] El Salvador (Roman Catholic Church building),[90] England (Church building of England),[91] Georgia (Georgian Orthodox Church building), Greece (Church of Hellenic republic), Iceland (Church of Republic of iceland),[92] Liechtenstein (Roman Catholic Church),[93] Malta (Roman Cosmic Church),[94] Monaco (Roman Catholic Church),[95] Romania (Romanian Orthodox Church), Kingdom of norway (Church of Kingdom of norway),[96] Vatican City (Roman Catholic Church),[97] Switzerland (Roman Catholic Church, Swiss Reformed Church and Christian Catholic Church building of Switzerland).

Number of adherents [edit]

The estimated number of Christians in the globe ranges from ii.2 billion[98] [99] [100] [101] to two.4 billion people.[b] The faith represents approximately one-third of the world'due south population and is the largest faith in the earth,[102] with the 3 largest groups of Christians beingness the Catholic Church, Protestantism, and the Eastern Orthodox Church.[103] The largest Christian denomination is the Catholic Church, with an estimated 1.two billion adherents.[104]

| Tradition | Followers | % of the Christian population | % of the world population | Follower dynamics | Dynamics in- and outside Christianity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catholic Church | 1,094,610,000 | 50.1 | 15.9 | | |

| Protestantism | 800,640,000 | 36.7 | 11.half dozen | | |

| Orthodoxy | 260,380,000 | 11.9 | 3.eight | | |

| Other Christianity | 28,430,000 | 1.three | 0.4 | | |

| Christianity | 2,184,060,000 | 100 | 31.7 | | |

Notable Christian organizations [edit]

A religious order is a lineage of communities and organizations of people who live in some way set autonomously from society in accordance with their specific religious devotion, usually characterized by the principles of its founder's religious practise. In contrast, the term Holy Orders is used by many Christian churches to refer to ordination or to a group of individuals who are set apart for a special role or ministry building. Historically, the word "order" designated an established civil body or corporation with a bureaucracy, and ordination meant legal incorporation into an ordo. The word "holy" refers to the Church. In context, therefore, a holy order is set autonomously for ministry in the Church building. Religious orders are composed of initiates (laity) and, in some traditions, ordained clergies.

Various organizations include:

- In the Roman Catholic Church building, religious institutes and secular institutes are the major forms of institutes of consecrated life, similar to which are societies of apostolic life. They are organizations of laity or clergy who live a common life under the guidance of a fixed rule and the leadership of a superior. (ed., see Category: Catholic orders and societies for a particular listing.)

- Anglican religious orders are communities of laity or clergy in the Anglican churches who live under a mutual dominion of life. (ed., see Category: Anglican organizations for a particular listing)

Christianity law and ethics [edit]

Church and land framing [edit]

Within the framework of Christianity, there are at least iii possible definitions for Church law. One is the Torah/Mosaic Law (from what Christians consider to exist the Old Testament) also called Divine Law or Biblical law. Another is the instructions of Jesus of Nazareth in the Gospel (sometimes referred to as the Law of Christ or the New Commandment or the New Covenant). A third is canon constabulary which is the internal ecclesiastical law governing the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox churches, and the Anglican Communion of churches.[106] The way that such church building constabulary is legislated, interpreted and at times adjudicated varies widely among these three bodies of churches. In all iii traditions, a canon was initially a rule adopted by a quango (From Greek kanon / κανών, Hebrew kaneh / קנה, for dominion, standard, or measure); these canons formed the foundation of canon law.

Christian ethics in general has tended to stress the demand for grace, mercy, and forgiveness because of human weakness and developed while Early Christians were subjects of the Roman Empire. From the time Nero blamed Christians for setting Rome ablaze (64 AD) until Galerius (311 Advertizement), persecutions against Christians erupted periodically. Consequently, Early Christian ethics included discussions of how believers should chronicle to Roman authorization and to the empire.

Under the Emperor Constantine I (312-337), Christianity became a legal organized religion. While some scholars debate whether Constantine's conversion to Christianity was accurate or simply matter of political expediency, Constantine'southward decree made the empire safe for Christian practice and belief. Consequently, issues of Christian doctrine, ethics and church practise were debated openly, see for example the First Council of Nicaea and the First seven Ecumenical Councils. Past the fourth dimension of Theodosius I (379-395), Christianity had become the land organized religion of the empire. With Christianity in power, ethical concerns broaden and included discussions of the proper role of the state.

Return unto Caesar… is the get-go of a phrase attributed to Jesus in the synoptic gospels which reads in total, "Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar'due south, and unto God the things that are God's". This phrase has get a widely quoted summary of the human relationship between Christianity and secular say-so. The gospels say that when Jesus gave his response, his interrogators "marvelled, and left him, and went their fashion." Time has non resolved an ambiguity in this phrase, and people go on to interpret this passage to support various positions that are poles apart. The traditional division, carefully determined, in Christian thought is the state and church have separate spheres of influence.

Thomas Aquinas thoroughly discussed that human law is positive law which means that it is natural law applied by governments to societies. All human laws were to be judged by their conformity to the natural constabulary. An unjust constabulary was in a sense no law at all. At this point, the natural police force was not only used to pass judgment on the moral worth of diverse laws, merely also to make up one's mind what the police said in the first place. This could issue in some tension.[107] Tardily ecclesiastical writers followed in his footsteps.

Autonomous ideology [edit]

Christian republic is a political ideology that seeks to utilise Christian principles to public policy. It emerged in 19th-century Europe, largely under the influence of Catholic social didactics. In a number of countries, the democracy's Christian ethos has been diluted by secularisation. In practice, Christian republic is oftentimes considered bourgeois on cultural, social and moral issues and progressive on fiscal and economic problems. In places, where their opponents accept traditionally been secularist socialists and social democrats, Christian democratic parties are moderately conservative, whereas in other cultural and political environments they can lean to the left.

Women's roles [edit]

Attitudes and behavior about the roles and responsibilities of women in Christianity vary considerably today as they have throughout the last two millennia — evolving along with or counter to the societies in which Christians have lived. The Bible and Christianity historically have been interpreted equally excluding women from church leadership and placing them in submissive roles in marriage. Male leadership has been assumed in the church and within union, society and government.[108]

Some contemporary writers describe the role of women in the life of the church as having been downplayed, overlooked, or denied throughout much of Christian history. Paradigm shifts in gender roles in society and also many churches has inspired reevaluation by many Christians of some long-held attitudes to the opposite. Christian egalitarians have increasingly argued for equal roles for men and women in matrimony, equally well as for the ordination of women to the clergy. Contemporary conservatives meanwhile have reasserted what has been termed a "complementarian" position, promoting the traditional conventionalities that the Bible ordains unlike roles and responsibilities for women and men in the Church and family unit.

Encounter also [edit]

- Caesaropapism – Social order combining secular and religious powers

- Christian republic – Regime that is both Christian and republican

- The City of God – Book by Augustine of Hippo

- Constantine the Bully and Christianity

- Constantinian shift

- Dominion theology – Ideology seeking Christian rule

- Ecumenism – Cooperation betwixt Christian denominations

- Holy Roman Emperor – Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire

- Integralism – Principle that the Catholic Faith should exist the basis of public police and policy

- Res publica Christiana

- Role of Christianity in civilization – Function of Christianity in civilization

- Union of Christendom, a traditional Catholic view of ecumenism

Notes [edit]

- ^ In 529, Justinian airtight the Neoplatonic Academy of Athens, a last bulwark of heathen philosophy, fabricated rigorous efforts to exterminate Arianism and Montanism, personally campaigned confronting Monophysitism, and made Chalcedonian Christianity the Byzantine land religion.[21]

- ^ Current sources are in full general agreement that Christians make up about 33% of the world's population—slightly over 2.4 billion adherents in mid-2015.

References [edit]

- ^ a b See Merriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"

- ^ Marty, Martin (2008). The Christian Earth: A Global History. Random House Publishing Group. p. 42. ISBN978-i-58836-684-nine.

- ^ a b c Hall, Douglas John (2002). The Finish of Christendom and the Future of Christianity. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. ix. ISBN9781579109844 . Retrieved 28 Jan 2018.

"Christendom" [...] means literally the dominion or sovereignty of the Christian religion.

- ^ Chazan, Robert (2006). The Jews of Medieval Western Christendom: 1000-1500. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. eleven. ISBN9780521616645 . Retrieved 26 Jan 2018.

- ^ Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "christendom. §1.three Scheidingen". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- ^ Chazan, p. 5.

- ^ a b Dawson, Christopher; Olsen, Glenn (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). ISBN978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ^ Eastward. McGrath, Alister (2006). Christianity: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. p. 336. ISBN1405108991.

- ^ a b "Review of How the Catholic Church Congenital Western Civilisation by Thomas Forest, Jr". National Review Book Service. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2010). A History of Christianity: The Showtime 3 Thou Years. London: Penguin Publishing Group. p. 572. ISBN9781101189993 . Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ "Translate christendom from Dutch to English".

- ^ "CHRISTENTUM - Translation in English - bab.la".

- ^ "Christendom | Origin and meaning of christendom past Online Etymology Lexicon".

- ^ a b c d Curry, Thomas John (2001). Farewell to Christendom: The Future of Church and Land in America . Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN9780190287061 . Retrieved 28 Jan 2018.

- ^ a b MacCulloch (2010), p. 1024–1030.

- ^ Debnath, Sailen (2010). Secularism: Western And Indian. ISBN978-81-269-1366-iv.

- ^ a b Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crunch in Western Education (reprint ed.). p. 108. ISBN9780813216836.

- ^ Acts three:1; Acts five:27–42; Acts 21:xviii–26; Acts 24:5; Acts 24:14; Acts 28:22; Romans 1:sixteen; Tacitus, Annales xv 44; Josephus Antiquities xviii 3; Mortimer Chambers, The Western Feel Volume II chapter five; The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion page 158[ failed verification ].

- ^ Walter Bauer, Greek-English Lexicon; Ignatius of Antioch Letter of the alphabet to the Magnesians ten, Letter to the Romans (Roberts-Donaldson tr., Lightfoot tr., Greek text). Notwithstanding, an edition presented on some websites, one that otherwise corresponds exactly with the Roberts-Donaldson translation, renders this passage to the interpolated inauthentic longer recension of Ignatius'south letters, which does not incorporate the word "Christianity."

- ^ Robert Peel (eighteen Feb 1981). "Impish defense force of Christianity; The End of Christendom, by Malcolm Muggeridge". The Christian Science Monitor . Retrieved 28 Jan 2018.

- ^ Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Justinianus I". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- ^ a b Hall (2002), p. one–nine.

- ^ Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Printing. pp. 699–701, see page 700, para 2, one-half manner down.

The whole issue had, in fact, become confused with the confusion of functions of the Church building and State. In the view of the Church of England the ultimate governance of the Christian community, in things spiritual and temporal, was vested non in the clergy merely in the "Christian prince" as the vicegerent of God.

- ^ The church in the Roman empire earlier A.D. 170, Part 170 By Sir William Mitchell Ramsay

- ^ Boyd, William Kenneth (1905). The ecclesiastical edicts of the Theodosian lawmaking, Columbia University Press.

- ^ Challand, Gérard (1994). The Fine art of War in Earth History: From Antiquity to the Nuclear Age. Academy of California Printing. p. 25. ISBN978-0-520-07964-9.

- ^ Willis Mason Due west (1904). The ancient world from the primeval times to 800 A.D. ... Allyn and Salary. p. 551.

- ^ Peter Brown; Peter Robert Lamont Brown (2003). The Ascent of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity 200-thousand AD. Wiley. p. 443. ISBN978-0-631-22138-8.

- ^ a b c Durant, Volition (2005). Story of Philosophy. Simon & Schuster. ISBN978-0-671-69500-2 . Retrieved 10 Dec 2013.

- ^ Shaping a global theological mind By Darren C. Marks. Page 45

- ^ Somerville, R. (1998). Prefaces to Canon Police books in Latin Christianity: Selected translations, 500-1245; commentary and translations. New Haven [u.a.: Yale Univ. Press

- ^ VanDeWiel, C. (1991). History of canon law. Leuven: Peeters Press.

- ^ Canon law and the Christian community By Clarence Gallagher. Gregorian & Biblical BookShop, 1978.

- ^ Cosmic Church., Canon Law Society of America., Catholic Church., & Libreria editrice vaticana. (1998). Code of canon police force, Latin-English edition: New English translation. Washington, DC: Canon Law Society of America.

- ^ Mango, C. (2002). The Oxford history of Byzantium. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Angold, M. (1997). The Byzantine Empire, 1025-1204: A political history. New York: Longman.

- ^ Schevill, Ferdinand (1922). The History of the Balkan Peninsula: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Harcourt, Caryatid and Visitor. p. 124.

- ^ Schaff, Philip (1878). The history of creeds. Harper.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Cosmic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ MacCulloch (2010), p. 625.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Cosmic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Stump, P. H. (1994). The reforms of the Council of Constance, 1414-1418. Leiden: Due east.J. Brill

- ^ The Cambridge Modern History. Vol two: The Reformation (1903).

- ^ Norris, Michael (August 2007). "The Papacy during the Renaissance". The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art . Retrieved 11 Dec 2013.

- ^ McGinness, Frederick (26 August 2011). "Papal Rome". Oxford Bibliographies . Retrieved xi December 2013.

- ^ Cheney, Liana (26 August 2011). "Background for Italian Renaissance". University of Massachusetts Lowell. Archived from the original on xvi January 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b Santayana, George (1982). The Life of Reason. New York: Dover Publications. Retrieved 10 Dec 2013.

- ^ This was presaging the modern nation-state

- ^ "The Anglican Domain: Church History".

- ^ Uwe Becker, Europese democratieën: vrijheid, gelijkheid, solidariteit en soevereiniteit in praktijk

- ^ "Wars of Religion". Britannica Online. June 26, 2021. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Koch, Carl (1994). The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. Early on Middle Ages: St. Mary'due south Printing. ISBN978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. The Age of Enlightenment: St. Mary'southward Press. ISBN978-0-88489-298-iv.

- ^ Rüegg, Walter: "Foreword. The University as a European Institution", in: A History of the University in Europe. Vol. ane: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-ii, pp. xix–xx

- ^ Verger 1999

- ^ "Valetudinaria". broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk . Retrieved 2018-02-22 .

- ^ Risse, Guenter B (April 1999). Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN978-0-nineteen-505523-viii.

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11. Auflage (1956), Tübingen (Frg), pp. 317–319, 325–326

- ^ Britannica.com Forms of Christian didactics

- ^ Rüegg, Walter: "Foreword. The University as a European Institution", in: A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. XIX–XX

- ^ Verger, Jacques (1999). Culture, enseignement et société en Occident aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles (in French) (1st ed.). Presses universitaires de Rennes in Rennes. ISBN978-2868473448 . Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Susan Elizabeth Hough, Richter's Scale: Measure of an Earthquake, Measure of a Homo, Princeton University Printing, 2007, ISBN 0691128073, p. 68.

- ^ Forest 2005, p. 109. sfn error: no target: CITEREFWoods2005 (assistance)

- ^ Britannica.com Jesuit

- ^ Britannica.com Church building and social welfare

- ^ Britannica.com Intendance for the sick

- ^ Britannica.com Belongings, poverty, and the poor,

- ^ Weber, Max (1905). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Commercialism.

- ^ Cf. Jeremy Waldron (2002), God, Locke, and Equality: Christian Foundations in Locke's Political Idea, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (United kingdom), ISBN 978-0-521-89057-ane, pp. 189, 208

- ^ Britannica.com Church and state

- ^ Sir Banister Fletcher, History of Architecture on the Comparative Method.

- ^ Buringh, Eltjo; van Zanden, Jan Luiten: "Charting the 'Ascension of the W': Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries", The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 69, No. 2 (2009), pp. 409–445 (416, tabular array 1)

- ^ Eveleigh, Bogs (2002). Baths and Basins: The Story of Domestic Sanitation. Stroud, England: Sutton.

- ^ Christianity in Action: The History of the International Salvation Army p.16

- ^ Britannica.com The tendency to spiritualize and individualize matrimony

- ^ Chadwick, Owen p. 242.

- ^ Hastings, p. 309.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Cosmic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Alfred Crosby described some of this technological revolution in his The Measure of Reality : Quantification in Western Europe, 1250–1600 and other major historians of technology have also noted it.

- ^ Harrison, Peter (viii May 2012). "Christianity and the ascension of western scientific discipline". Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Noll, Marker, Science, Faith, and A.D. White: Seeking Peace in the "Warfare Between Scientific discipline and Theology" (PDF), The Biologos Foundation, p. four, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2015, retrieved 14 January 2015

- ^ Lindberg, David C.; Numbers, Ronald L. (1986), "Introduction", God & Nature: Historical Essays on the Run across Between Christianity and Science, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 5, 12, ISBN978-0-520-05538-4

- ^ Gilley, Sheridan (2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 8, World Christianities C.1815-c.1914. Brian Stanley. Cambridge University Printing. p. 164. ISBN0521814561.

- ^ Britannica Book of the Yr 2010. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 2010. p. 300. ISBN9781615353668 . Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ "The Size and Distribution of the World'south Christian Population". 2011-12-nineteen.

- ^ "Argentina". Britannica.com . Retrieved 11 May 2008.

- ^ "Gov. Pataki Honors 1700th Ceremony of Armenia'southward Adoption of Christianity equally a state religion". Aremnian National Committee of America. Archived from the original on 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2009-04-11 .

- ^ "Costa Rica". Britannica.com . Retrieved 2008-05-11 .

- ^ "Kingdom of denmark". Britannica.com . Retrieved 2008-05-xi .

- ^ "Republic of el salvador". Britannica.com . Retrieved 2008-05-11 .

- ^ "Church and State in United kingdom: The Church of privilege". Eye for Citizenship. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2008-05-xi .

- ^ "Iceland". Britannica.com . Retrieved 2008-05-eleven .

- ^ "Liechtenstein". U.S. Section of Country. Retrieved 2008-05-11 .

- ^ "Republic of malta". Britannica.com . Retrieved 2008-05-11 .

- ^ "Monaco". Britannica.com . Retrieved 2008-05-11 .

- ^ "Norway". Britannica.com . Retrieved 2008-05-xi .

- ^ "Vatican". Britannica.com . Retrieved 2008-05-eleven .

- ^ 33.39% of ~7.2 billion world population (under the section 'People') "World". CIA world facts.

- ^ "Christianity 2015: Religious Diverseness and Personal Contact" (PDF). gordonconwell.edu. Jan 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-05-25. Retrieved 2015-05-29 .

- ^ "Major Religions Ranked by Size". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on Baronial 16, 2000. Retrieved 2009-05-05 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Assay (2011-12-19). "Global Christianity". Pewforum.org. Retrieved 2012-08-17 .

- ^ "Major Religions Ranked by Size". Adherents. Archived from the original on August xvi, 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-31 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Hinnells, The Routledge Companion to the Written report of Religion, p. 441.

- ^ "How many Roman Catholics are at that place in the globe?". BBC News. March fourteen, 2013. Retrieved 2016-x-05 .

- ^ "Global Christianity – A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World'southward Christian Population". 19 Dec 2011.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Visitor.

- ^ Burns, "Aquinas's Two Doctrines of Natural Law."

- ^ Blevins, Carolyn DeArmond, Women in Christian History: A Bibliography. Macon, Georgia: Mercer Univ Press, 1995. ISBN 0-86554-493-Ten

Bibliography [edit]

- 20th century sources

- The Render of Christendom. Macmillan. 1922.

- Andrew Dickson White (1897). A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. D. Appleton.

- F. G. Cole (1908). Mother of All Churches: A Brief and Comprehensive Handbook of the Holy Eastern Orthodox Church. Skeffington.

- 19th century sources

- Hull, Moses. Encyclopedia of Biblical Spiritualism; Or, A Cyclopedia to the Main Passages of the Old and New Testament Scriptures Which Show or Imply Spiritualism; Together with a Brief History of the Origin of Many of the Important Books of the Bible. Chicago: Chiliad. Hull, 1895. (ed., reprint version is available)

- Bosanquet, Bernard. The Civilization of Christendom, And Other Studies. London: S. Sonnenschein, 1893.

- The History of Teachings of the Early Church, as a Ground for the Re-union of Christendom: Lectures. Eastward. & J. B. Young. 1893.

- John Hodson Egar (1887). Christendom; ecclesiastical and political, from Constantine to the Reformation. J. Pott.

- The Churches of Christendom. Macniven and Wallace. 1884.

- Charles, Elizabeth (1880). Sketches of the women of Christendom, by the author of 'Chronicles of the Schönberg-Cotta family unit' .

- Naville, Ernest (1880). The Christ: 7 lectures. T. & T. Clark.

- George William Cox (1870). Latin and Teutonic Christendom: An Historical Sketch. Longmans, Greenish & Company.

- Girdlestone, Charles (1870). Christendom, sketched from history in the light of holy Scripture. Published for the Author by Sampson Low, Son, & Marston.

- John Radford Thomson (1867). Symbols of Christendom: an uncomplicated text-book.

- Thomas William Allies (1865). The formation of Christendom. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Dark-green.

- Stearns, George (1857). The mistake of Christendom; or, Jesus and His Gospel before Paul and Christianity. B. Marsh.

- Johnson, Richard (1824). The Renowned History of the Seven Champions of Christendom: St. George of England, St. Denis of France, St. James of Kingdom of spain, St. Anthony of Italian republic, St. Andrew of Scotland, St. Patrick of Ireland, and St. David of Wales, and Their Sons. W. Baynes.

Further reading [edit]

- Bainton, Roland H. (1966). Christendom: a Brusque History of Christianity and Its Touch on Western Civilization, in series, Harper Colophon Books. New York: Harper & Row. ii vol., ill.

- Molland, Einar (1959) Christendom: the Christian churches, their doctrines, constitutional forms and ways of worship. London: A. & R. Mowbray & Co. (commencement published in Norwegian in 1953 as Konfesjonskunnskap).

- Whalen, Brett Edward (2009). Dominion of God: Christendom and Apocalypse in the Eye Ages. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Academy Press.

External links [edit]

| | Expect upwardly Christendom in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Websites

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Visitor.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christendom

0 Response to "what is the position in the world today of nations that are heirs to european christendom?"

Post a Comment